History of Fresco Painting II

Cimabue: the hidden master

The Italian masters

The most celebrated wall art in Western Europe was painted by great Italian masters: Giotto, Michelangelo, Raffaello and Tiepolo. Giotto’s medieval frescoes in the Arena (or Scrovegni) Chapel at Padua (1305-06) revolutionized the depiction of Christ and other biblical figures by expressing the human quality of their suffering; Renaissance fresco masterpieces, such as Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel ceiling (1508-12) and Raffaello’s School of Athens in the Vatican (1510-11), are renowned for their enormous size, expressive power, and elaborate beauty. Tiepolo’s mural art, painted in the Rococo style of the 1700s, is lighter and more playful.

Giotto

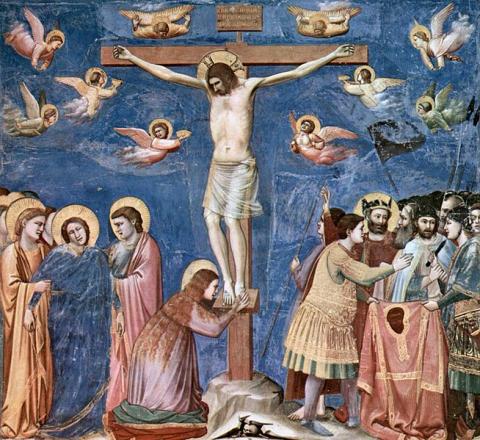

Giotto, the founder of modern painting: Crucifixion

Giotto is regarded by many as the founder of modern painting and a large majority of his work was produced using fresco technique. The first example of his majestic work to come into mind are the Franciscan fresco cycles in the Basilica Superiore and Basilica Inferiore in Assisi.

Giotto lived through the great mural art revival that hit Italy in the 13th and 14th century, possibly also influenced by his master Cimabue who, however, did work on other means, too.

In scale and scope, wall painting was the most important art form in 14th century Italy. Giotto’s large artwork in the Scrovegni Chapel in Padua is among the most perfectly preserved examples of fresco painting. Giotto used both buon fresco and affresco a secco techniques for the Scrovegni Chapel: in the first, pigments are applied directly on wet plaster, in the second they are used with a binder on dry wall.

It is likely that, for a design as complicated yet unified as Giotto’s Scrovegni Chapel, extensive preparatory drawings were done since the technique makes alterations or changes difficult. In fact, we know today that working sketches are an essential part of the frescoing technique.

Giotto is an essential figure in the history of Italian and world art because he carried on further those innovations already embraced by Cimabue. Giotto finally donates full plasticity to painted bodies, in opposition with the flat regularity of Greek-Byzantine works. He exalts to modern levels expressivity and emotions in his figures, he goes back, therefore (also through the example of Cimabue) to a typical feature of Roman figurative art. The construction of space in his paintings becomes more realistic and the color palette changes, diminishing the presence of Byzantine gold in favor of hues of beautiful blues, reds and pinks.

Tiepolo

Giambattista Tiepolo: an expression of opulence and uncertainty

The Venice in which Giambattista Tiepolo was born and reared was a state facing political and economic decline, after centuries of splendor. We are in the 18th century, and the Venetian Republic had lost supremacy of the seas following the Turkish conquest of Candia. The Hapsburg Empire prevented transport and movement by land, and Venice was also largely by-passed in the game of alliances that was to form the basis for a new political order in Europe.

The most influent families of the Republic, however, failed to understand and accept this new, prevailing reality: every palace on the Grand Canal, every villa in the beautiful countryside surrounding the city, continued to be the centre of a lavish, at times fatuous lifestyle. Reality was a far away nightmare that rich Venetians kept at bay by reveling in luxury and by seeking refuge in the past. Nobility in particular failed to face its decadence by finding refuge in the fasts and beauty of the Classics. Rome and Athens, their history and myths, became source of inspiration and reason of imitation for the artists of the time, their aesthetic canons returning powerfully to the lead of visual and figurative arts.

The rest of Venetian society, however, was much more aware of its surrounding and dealt with difficulties by exorcising them through art: this is the century when the Teatro dell’Arte, where traditional Italian masks were born, became famous, its aesthetics leaving a mark on the century’s ideal of beauty and artistic production.

This dichotomy has never been as evident as in the relationship between the two Tiepolos, father and son: Giambattista, the father, fresco painter and lover of the grandiosity of classical mythology, and his son Giandomenico, creator and decorator of Venetian teatro dell’arte masks. A type of art, that of Giandomenico, steeped in the disenchanted and at times grotesque reality of his time.

Tiepolo father was born in Venice, probably on the 5th of March 1696, the youngest of six children. His family was wealthy, and during his entire life he was successful in his profession, earning prestige and recognition for his frescoes.

Initially, Tiepolo was an apprentice in the studio of a minor master, but soon became acquainted with the masters of the tormented, dark aesthetics of 17th century realism. At age twenty, Tiepolo painted The Sacrifice of Isaac and The Martyrdom of Saint Bartholomew. However, after these two early pieces, he did not stick with such somber tones. He, on the contrary, moved onto a freer use of colors and became a fresco expert. The Church of the Carmelitani Scalzi in Venice, is one of its best known works of this type: for the first time in the decorative painting of the 18th century, skies are painted to appear free and luminous, while figures tend to move toward the margins of the ornate and precious frames of the image.

Tiepolo becomes the painter of skies, of clouds, of angels and of groups and compositions of figures.

He soon, too, developed a taste for historical and mythological subjects, placing them against a background of elegant fantasy. Not even his city, Venice, managed to provide real inspiration for his work: Tiepolo barely worked on natural, real life paintings, preferring the recreation of literary or mythical atmospheres, essential to evade reality and take refuge in the sublime.

Frescoes today

Fresco painting has been attracting renewed interest and acclaim. In addition, the technique's emphasis on natural materials and skilled artistry may appeal to a world weary of mass production and disposable goods. The fact some of the most famous paintings in the world are frescoes (think of the Creation of Man and the Last Judgment in the Sistine Chapel, or the Last Supper), may also have influenced the rise in popularity of this type of artistic production.

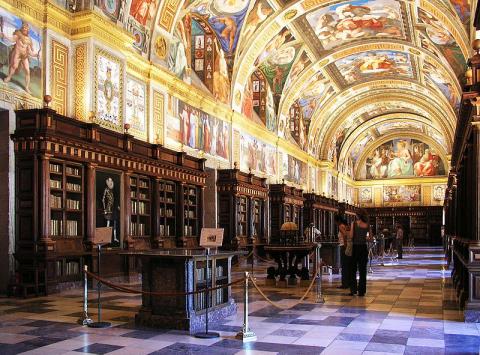

Frescoes from El Escorial, Madrid.